Sincerely,Dear Readers: My book is now in print, but my research on Edward Hitchcock continues. On this page I will periodically pass along new information, insights, and anecdotes from my research that I hope will be of interest.

December 19, 2025

EDWARD HITCHCOCK ONCONNECTICUT’S MINERAL RESOURCES

Edward Hitchcock was a true pioneer in American science, garnering many firsts in the fields of geology and paleontology in the young nation. He was the first American geologist to carry out a state-funded geological survey (1830-1833); the first to find evidence of dinosaurs in North America (1835); the first to publicly embrace the theory of continental glaciation (1841). Several of his published works were firsts as well. He was the first scientist to publish a study of the geology of Martha’s Vineyard (1824), the first to study the geology of Rhode Island (1830-1833), and the first to elucidate the process of metamorphism in rocks (1861).

An early draft of Hitchcock's geological map of Connecticut, drawn and hand-painted by Orra White Hitchcock (Courtesy Amherst College Archives and Special Collections).

While Edward Hitchcock's name is most often associated with Massachusetts, he was also a pioneer in studying the geology of Connecticut. In 1824 his article, “A Sketch of the Geology, Mineralogy, and Scenery of the Regions Contiguous to the River Connecticut,” appeared in the American Journal of Science. His “sketch” ran to 55,000 words, making it the longest article to appear in the first two decades of that journal. Not only was it the first detailed geological study ever undertaken in Connecticut, it became a template for Hitchcock’s later surveys in Massachusetts and Vermont. Orra’s beautiful, hand-colored map that accompanied that article was something of a first as well (see an early draft above).Among the interesting geological findings Hitchcock reported in that 1824 article are descriptions of some of the Constitution State’s mineral resources. And here I found some “Fun Facts” of Connecticut geology that surprised me and I hope will interest you, my readers.

Connecticut Marble in the White House

First, did you know that Connecticut at one time produced some of the finest marble in the world? Verd antique is a beautiful green marble with bands of darker serpentine swirling through it. Hitchcock found only two quarries of verd antique in the entire state, one in Milford, the other in West Haven. “From these are obtained a marble which vies for elegance with any in the world,” wrote Hitchcock in that 1824 article. It was so exceptional that it was used in many of the finest homes in New Haven and found its way into the Smithsonian Museum and the White House in Washington, DC. I wonder if any of that wonderful Connecticut stone survived the recent demolition of “The People’s House.”

Connecticut Sandstone in New York City

Hitchcock also described a variety of red sandstone with a brownish tinge that was found from East Haven north to Manchester. “This rock is extensively quarried for the purpose of building, in almost every town along the river,” wrote Hitchcock. “Noble specimens may be seen in the vestibules of the churches in New-Haven.” It later became known as “brownstone,” giving its name to many homes constructed of it in New York City.

New York City "brownstones"

Greenstone - Connecticut's Most Valuable Mineral Resource

Hitchcock was well familiar greenstone, another of central Connecticut’s most distinctive rock formations, because he found it in abundance along the Deerfield Range that loomed over his hometown of Deerfield, Massachusetts. He described the character of this rock at some length including its distinctive polyhedral columns: “They have from three to six sides, are articulated, the points varying from one to three feet in diameter, and of the same height, exhibiting handsome convexities and corresponding concavities.” Repeated freezing and thawing caused those columns to crumble, forming great piles at their base.In his 1833 report on the Massachusetts survey he wrote, “This is one of the most enduring of all rocks, but it is usually so much divided by irregular seams, into small and shapeless blocks that it is but little employed, either in the construction of houses, or walls.” Wouldn’t he be surprised (as was I) to discover that greenstone, better known today as “traprock,” was by the mid-twentieth century widely used in asphalt. Today it ranks as by far the most valuable mineral quarried in both Connecticut and Massachusetts!

A trap rock ridge

Coal - Connecticut's LEAST Valuable Mineral Resource

Hitchcock was perhaps the first to debunk a myth about Connecticut’s mineral resources. Rumors abounded in his day about valuable coal resources buried beneath the surface of the state of Connecticut. Hitchcock did find coal in East Haven, Southington, Berlin, Durham, Middletown, Chatham, Hartford, Wethersfield, Somers, Ellington, and Suffield. The quality was good, he explained, but “The seams of it are usually quite thin, rarely exceeding an inch in thickness, yet often they are numerous.” Coal in Connecticut there was, but alas, nothing worth mining. Bad luck, Connecticut...or given the history of the coal industry elsewhere, perhaps we should say, good luck, Connecticut.

+ + + +

My article, “Granite, Greenstone, and Geest: Edward Hitchcock and the Geology of Connecticut,” is scheduled to appear in the spring 2026 issue of the Connecticut History Review. It will tell the long-forgotten story of how a young, unknown Bay State preacher came to publish such an important and influential work on the geology of the Constitution State. If you are interested, watch this space as I plan to insert a link to that article as soon as it appears in print.

June 20, 2025

JAWS: The Sequel

"We're gonna need a MUCH bigger boat!"

If you are a movie fanatic, I don't have to remind you of the important anniversary observed this month. It was fifty years ago, on June 20, 1975, that "Jaws" premiered in theaters around the country. It was directed by a 27-year-old named Steven Spielberg and based on the book by Peter Benchley. Much of the filming took place on Martha's Vineyard. Many natives can remember those days - some even appeared as extras.

What does that epic horror film have to do with Edward Hitchcock, you ask? Hitchcock was the first geologist to study the geology of Martha's Vineyard during a short visit to the island in 1823. The following year he published an article on the subject in the American Journal of Science entitled "Notices on the Geology of Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts."

Hitchcock reported on three major geological formations of the Vineyard, the Alluvial Formation on the south, the Diluvial Formation to the north and northwest, and what he termed the "Plastic Clay Formation" to the west, borrowing a term from British geology of those times. On that first trip he was unable to travel to Gay Head where he knew the largest part of that clay formation would be found.

Seven years later Hitchcock made up for that omission, making a special trip by steamer from Falmouth to Gay Head. He wrote,

The most interesting spot on Martha's Vineyard is Gay Head; which constitutes the western extremity of this island, and consists of clays and sands of various colors. Its height cannot be more than 150 feet; yet its variegated aspect, and the richness of its colors, render it a striking and even splendid object, when seen from the ocean. Every lover of natural scenery would be delighted to visit this spot. There is nothing to compare with it in New England.

(Source: E. Hitchcock, Report on the Geology, Mineralogy, Botany, and Zoology of Massachusetts, 1833.)

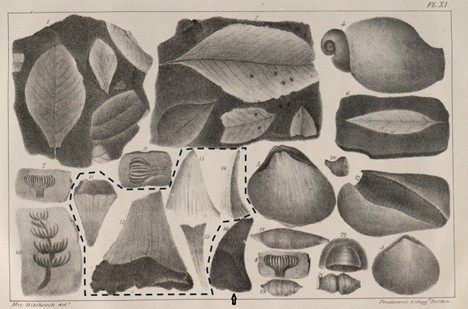

He spent three days collecting over 100 specimens at the Gay Head Cliffs including red, green, yellow, white, and brown clays, partially carbonized wood known as lignite, fossilized leaves of willow and elm embedded in iron ore, and an unidentified seed pod. Animal remains included two species of bivalves, a sea snail, several crabs, vertebrate bones, shark teeth, and a crocodile tooth. Orra White Hitchcock drew this illustration that includes the five shark teeth (dashed line) and one crocodile tooth (#16) collected on that trip.

Source: Hitchcock, Plates Illustrating the Geology and Scenery of Massachusetts, (J. S. and C. Adams, 1833), Plate XI.

Based on the size of one of the shark teeth he found at Gay Head, Hitchcock estimated the length of the shark at thirty-six feet. That's some 11 feet longer than "Bruce," the plywood and Plexiglas model made for the filming of "Jaws," and nearly twice the size of the largest sharks known today. Hitchcock wrote, "Such was one of the animals that swam in the ancient seas of this latitude!"

Of the crocodile tooth and shark teeth he wrote:

The tooth of the crocodile at Gay Head, as well as the great size of some of the shark's bones, show, also, that when these animals swam in the waters of our continent, the climate must have approximated to a tropical character.

(Source: E. Hitchcock, Report on the Geology, Mineralogy, Botany, and Zoology of Massachusetts, 1833.)

So Edward Hitchcock might not be surprised to learn that, two centuries later, when Earth's climate is heating up once again, sharks are returning to the North Atlantic Coast. Who knows, perhaps crocodiles will soon be frequenting the bayous and sloughs of coastal New England!

For more information see my article, "Revelations in Stone: Edward Hitchcock and the Geology of Martha's Vineyard," in the Summer 2025 issue of the Martha's Vineyard Museum Quarterly.

March 13, 2025

A TALE OF TWO PORTRAITS

If you browse through the collections of the Mead Art Museum at Amherst College, you will find no fewer than seventeen portraits of that institution's early presidents. They include one portrait of most, such as Amherst's first president, Zephaniah Swift Moore, two of several others, Moore's successor, Heman Humphrey, and twentieth-century presidents George Olds and Stanley King.

Perhaps you are wondering which Amherst College president holds the record for most portraits in the Mead collection? You've probably already guessed the answer: Edward Hitchcock. No fewer than three portraits of Hitchcock can be found in the Mead's collections database. I find that a curious fact. Edward Hitchcock was not a vain man, and he eschewed all manner of self-glorification. When his 1861 autobiography was about to go to press, Hitchcock objected to the publisher's decision to include a portrait of the author - the publisher prevailed.

Recently two of those three Hitchcock paintings have come under scrutiny from art historian Emily Esser. She has combined her extensive knowledge of early American art with some good old-fashioned sleuthing to solve a mystery. It's not a murder or heist in the tradition of Miss Marple or Sherlock Holmes, it is a "who done it?" of a different sort.

One of the works in question is an informal view of Hitchcock seated in his study surrounded by his books and a decorative bowl that looks very much like a bird bath with several doves dabbling in its waters. Through the window the Holyoke Range may be seen in the distance. The exact date of that portrait is unknown, but Hitchcock looks relatively young, his face only slightly wrinkled with age. We might guess it was painted before he took over the presidency in 1845, before the stresses and strains of that office began to take their toll on him.

For decades the Mead Art Museum listed that painting as the work of a German portraitist identified as William Rohner. But Ms. Esser questioned that attribution on the basis of both circumstances and style. She concluded that it was the work of Deacon Robert Peckham of Westminster, Mass., a well-known and accomplished portraitist in his day.

Robert Peckham was a friend of both Edward and Orra Hitchcock; he and his wife lived for several years in Northampton; both couples were active in the anti-slavery movement in Massachusetts. The Peckhams' eldest son, Joseph, attended Amherst College in the mid-1830s. And Deacon Peckham painted "The Return" that portrayed the professor being greeted by his wife and children upon his return from a journey (see Chapter 15 of my biography of Edward Hitchcock). There is even a record of Deacon Peckham staying nearly two weeks at the Hitchcocks' home around 1840.

As to style, Ms. Esser has marshaled a wealth of data to show that the portrait is consistent with Peckham's work. Based on her detailed study, the Mead has re-attributed that portrait to Robert Peckham. Her article on the subject was recently published in an influential art journal (see below).

The second portrait in question is a much more formal work. While it was painted only perhaps 6 or 7 years after the Peckham portrait, the duties of the presidency had aged Hitchcock considerably. The Mead Art Museum had long listed the artist of this work as "unknown." But when Ms. Esser asked me if I had any information on it, I discovered a newspaper article that appeared in the Hampshire Gazette in June 1852. The college alumni had just held a reunion and in a report on that occasion, it was noted that the alumni had commissioned a portrait of President Hitchcock to be painted by a German artist named Wilhelm Roehner. Another mystery solved!

For decades Roehner had been incorrectly credited with the earlier portrait, but now it became clear that he was the painter of this later, more formal work. The newspaper article also reported that the painting, when completed, would be installed in the Morgan Library then under construction.

Lest there be any doubt which portrait that newspaper article refers to, a photograph of the library reading room taken some years later shows three presidential portraits side by side, Moore, Humphrey, and Hitchcock, and the latter is clearly the second, formal portrait. The style of that formal portrait is entirely consistent with Roehner's other works. Once again Ms. Esser's investigations convinced the Mead; they have since reassigned that portrait to Wilhelm Roehner.

You may recall from Chapter 21 of my book that when the Hitchcocks traveled to Europe in 1850, Edward acquired an aneroid barometer. He was very proud of that instrument and used it to determine the altitudes of mountains in Wales and Switzerland. If you look closely at that 1851 portrait, you will see further confirmation of the value of that instrument to President Hitchcock. For he holds in his hands his beloved aneroid barometer.

What about that third Hitchcock portrait? It is attributed to John Ellis Bird (1873-1970), a Massachusetts-born artist who lived much of his life in the Boston area and worked for a time at MIT. But how could Bird have painted a portrait of a man who died before he was born, you might well ask? As far as I can tell, Bird painted the Hitchcock portrait from an 1859 photograph. Exactly when it was executed is not known, but it was acquired by the Mead in 1908. What was Bird's connection to Amherst? It turns out that his brother, George Kurtz Bird, graduated from Amherst in 1897. Bird also painted two other portraits that are in the Mead collection. Another painting attributed to Bird is a stunning portrait of President Julius H. Seelye. It has a date of 1880. Unless Bird was an artistic prodigy, it seems that portrait will require more art sleuthing.

For more on Emily Esser's investigation I recommend her recent article, "Stone Birds: How to Find a Peckham." It's in the March 2025 issue of Maine Antique Digest, pp. 54-7. Here is a link. You may also want to visit her blog, "Paintings Worth Looking At."

December 12, 2024

BOWLDERS, PEBBLES, AND LUMPS

What was it about the geology of Rhode Island

that intrigued Edward Hitchcock?

Edward Hitchcock's geological survey of Massachusetts was an important milestone in North American geology. The first comprehensive survey undertaken by any state, it became a model replicated by dozens of other states over the coming decades.

But in reading Hitchcock's 400-page field notes from that survey, I discovered something curious about his itinerary. On August 2, 1830, barely five days into his very first foray, he crossed the state line from Uxbridge, Massachusetts, into Rhode Island. He spent the next three days traveling around the Ocean State, from Smithfield southward to Johnston, Providence, and Bristol, then northward again to Pawtucket. Along the way he visited mines and quarries, talked to residents and workers, collected specimens, and made copious notes and sketches of what he observed. Before that survey was completed, he visited Rhode Island two additional times, in 1832 and 1833, spending perhaps ten days in all.

Now Edward Hitchcock was frugal to a fault, especially when on the state payroll, so as I read of his travels in Rhode Island I felt certain that he was not on some junket or joy ride. There had to be a method to the professor's meanderings, a scientific purpose that drove him as much as 30 miles beyond the Massachusetts state border. It soon became clear what he found so interesting "south of the border" - it was coal.

A coal mine in Cranston, RI.

(Image courtesy of Cranston Historical Society)

Coal deposits had been known in Rhode Island for at least seventy years when Hitchcock began his survey. During his visits Hitchcock saw anthracite being mined in Portsmouth, Bristol, and Cumberland. The coal deposits at Cumberland were of particular interest as they lay within a few miles of the state line. Hitchcock was convinced that they extended into nearby Massachusetts. A few months later he visited one coal deposit barely ten miles east of Cumberland at Mansfield, Massachusetts, and a small abandoned mine some thirty miles northwest in Worcester.

Rhode Island coal had a reputation as a low quality fuel, and there were indications that the several deposits in Massachusetts were no better. Nevertheless, Hitchcock was convinced that Bay State coal held promise for its citizens. In his final report he wrote of the Worcester coal,

"...in a country so wanting in coal as New England, a deposit of inferior coal is not to be regarded as useless. The time will probably come when it will be regarded as very valuable."

Alas, that time never came. But the prospects for New England coal were not lost on 20th century geologists. In 1974 while a graduate student at Boston College, I can remember hearing the esteemed BC geologist Father James W. Skehan lecturing on the subject, suggesting that Rhode Island coal still held promise.

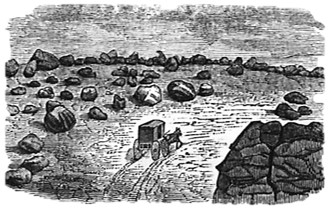

While it may have been coal that brought Hitchcock to Rhode Island in the first place, his time there was rewarded by two other geological features that proved highly instructive to the professor, "bowlders" and "flattened pebbles."

Again and again in Rhode Island, Hitchcock observed large boulders perched on bedrock of an entirely different type. In each case the nearest outcrop of bedrock that could possibly have been the source of the boulder was northward, often tens of miles distant. The most dramatic example was an outcrop of magnetic iron ore in Cumberland that he traced nearly 30 miles southward to Newport - you might call it the "mother of all boulder trains." Ever the astute observer, Hitchcock recorded this prescient comment in his notes of August 3, 1830,

"The north end of Rhode Island is a good place to teach the geologist not to rely on bowlders for the character of the formations."

Those huge isolated "bowlders" raised an important question for the Amherst professor: What "agency" (to use Hitchcock's own term) could have carried such massive artifacts great distances, often leaving a trail of smaller stones behind? That question perplexed Hitchcock until he read about the theory of continental glaciation as first published by Louis Agassiz a decade later. Hitchcock was immediately convinced and became the first American geologist to publicly embrace that theory.

It was on the rockbound wave-lashed coast at Middletown, Rhode Island, that Hitchcock first observed another geological curiosity of that state, what he described as "flattened pebbles cleft by Titan's sword." Once again his observations from Rhode Island helped Hitchcock to unravel a geological mystery, the process of metamorphism in rocks. (For more on those "flattened pebbles" please see my previous post below.)

By his own assertion Hitchcock was a "man of facts," devoted to observing and recording what he saw around him and beneath his feet. He was slow to draw conclusions, biding his time observing, pondering, striving to make sense of what he saw in his travels. How interesting it is to learn that for all his intensive studies of the surface geology of the Bay State over four field seasons, in just a week or two in Rhode Island he found what proved to be vital insights into some of the great geological enigmas of his day.

For more on the subject see my article, Revelations in Stone: Edward Hitchcock and the Geology of Rhode Island, in the Fall 2024 issue of the journal Rhode Island History. Click here to read the article.

June 18, 2024

EDWARD HITCHCOCK AND THE GEOLOGY

OF CAPE COD AND THE ISLANDS:

Reflections on a 200th Anniversary

In April 1823, Edward Hitchcock wrote to Professor Benjamin Silliman of Yale College asking his friend and mentor for advice as to a possible geological excursion for that spring:

I have thought some of the White Hills. But as the coast is better for my constitution I have been thinking of the islands of Nantucket & Martha's Vineyard. Can you tell me whether these would be probably interesting spots or are they all sand?

Silliman had no advice for his friend on that subject. But Hitchcock made a decision on his own, one that proved to be a watershed event in his life, both as a geologist and as a man of faith. And it may well have given him his earliest inkling of a coming revolution in American geology.

In early June, Edward Hitchcock visited Martha's Vineyard, and he quickly learned that it was far from "all sand." During his travels across the island in a horse-drawn chaise, he made notes for an article that would appear in the American Journal of Science the following year, the first detailed geological study of the Vineyard ever to appear in print.

As he traveled around the island, Hitchcock observed an "Alluvial Formation" to the south and a "Plastic Clay Formation" to the west. But the feature that most attracted his attention lay atop the clay. He wrote,

All the north western extent of the island is hilly and uneven with no abrupt precipices but rising into rounded eminences...

Strewn across that rolling terrain he observed a jumbled mantle of pebbles and stones of granite, gneiss, quartz, and mica. He named this the "Diluvial Formation," referring to material deposited by flood waters. Hitchcock regarded much of the surface geology of the earth as the result of the Great Flood of Genesis, the flood of Noah and his Ark. So when he assigned the label "diluvium" to that detritus, he was ascribing its deposition to that great biblical cataclysm, a conclusion with which most geologists of his day would concur.

Most striking of all to Hitchcock was "the quantity of huge bowlder stones, scattered over these hills on every side," some over 50 feet in diameter. At first he assumed these to be outcrops of the underlying bedrock. But the local inhabitants soon set him straight - there was, they assured him, no bedrock to be found anywhere on the island of Martha's Vineyard.

But if those huge boulders were not derived from the underlying bedrock, where had they come from? Here Hitchcock made a telling observation, one that would resonate among geologists worldwide over the coming decades. Those boulders, that diluvium, he asserted, must have been "derived from the rocks that occur in place along the coast, on the mainland."

Seven years later, Hitchcock, then Professor of Chemistry and Natural History at Amherst College, received an appointment as the first State Geologist of Massachusetts with the goal of surveying the state's untapped mineral resources. In July 1830 he set out on the first field excursion of that survey, traveling in a rickety horse-drawn wagon accompanied by one of his students. A month into their travels, they arrived on Cape Cod.

Hitchcock's first observations, not surprisingly, harked back to his earlier visit to the Vineyard:

From Sandwich to Barnstable 12 miles diluvium all the way. In many places the bowlders are enormously large weighing 100 to 200 tons and very thick. In short the face of the country and its geological character appear to be precisely like those of Martha's Vineyard and the Elizabeth Islands. I doubt not but the same remark will apply to the whole of Cape Cod.

On the mainland Hitchcock observed two other important features that reinforced his doubts about the origin of that so-called diluvium. Gouged in bedrock across New England he noted deep furrows, nearly all with the same orientation, from northwest to southeast. In addition he observed sinuous trains of large boulders, many extending tens of miles from their origin, all with similar orientations.

By 1833 Edward Hitchcock had seen more than enough evidence to make him skeptical of the "diluvial hypothesis."

Making every allowance for the reduction of the gravity of these bowlders when in water, I confess I cannot conceive how such a work could have been effected by this agency [by water].

Eight years later, in 1841, Edward Hitchcock stood before the members of the newly-formed Association of American Geologists in Philadelphia, and declared himself a convert to a stunning new notion, continental glaciation. It was not his theory, it was the work of Louis Agassiz, Jean de Charpentier, and other European scientists, and it had first appeared in Agassiz's landmark study, Etudes sur les Glaciers. Agassiz put forward the radical notion that ice, not water, was the primary agent responsible for sculpting much of the surface of the northern hemisphere, that a huge ice cap had accumulated in the northern polar regions, gradually expanding southward over hundreds of thousands of years. It was a glacier, or series of glaciers, of massive extent, and it gouged, scraped, and bulldozed the earth's surface as it advanced.

Hitchcock's ringing endorsement gave the theory wide exposure and credibility among American scientists, although there remained a good deal of resistance in some quarters - Hitchcock himself backpedaled and equivocated on the idea repeatedly. Nevertheless, the evidence was strong and compelling. By the 1860s the concept of continental glaciation had been accepted and embraced by most scientists in America and worldwide.

As to non-scientists, particularly theologians, members of the clergy, and other people of faith who were suspicious of new ideas in science, the fact that Reverend Edward Hitchcock, well known as a devout man of strict orthodox Christian views, was comfortable with such a notion may well have given them license to accept the theory.

Edward Hitchcock's life was a dual journey of faith, faith in God and faith in science. That journey led him to question some of the basic tenets of his religion as well as some of the fundamental scientific ideas of his day. And it all began with a visit to Martha's Vineyard in 1823 and the sight of those huge "bowlders" scattered over a sandy Chilmark plain.

In a sermon delivered to his congregation in 1822, Reverend Hitchcock warned his parishioners to pay heed to the world around them.

Let the unbeliever then remember that as he passes over our hills the very stones cry out against him.

The stones did cry out to Edward Hitchcock that day on Martha's Vineyard, and the message they bore was truly a revelation in stone.

==========

November 30, 2023

WAS EDWARD HITCHCOCK A GRINCH?

Reverend Edward Hitchcock often preached on the fundamentals of orthodox Christianity, subjects such as repentance, resurrection, and morality. Occasionally his sermons also addressed the great social issues of his day, war, slavery, the abrogation of the rights of Native Americans, and, of course, the consumption of ardent spirits.

But in my reading and transcription of Hitchcock's sermons, I was surprised to discover hardly a mention of one topic central to Christianity then and now, the birth of Jesus. In his more than 200 sermons, the word "Christmas" appears exactly once, in a sermon entitled "The Advent of Christ," his only sermon devoted to that topic.

Hitchcock first delivered his one and only Christmas sermon in Conway, Massachusetts, in January, 1823. According to his records he reused it on four subsequent occasions over the next thirteen years, all but one in the month of January.

Why did the birth of the savior receive so little attention from Reverend Hitchcock? And why did he preach on the subject only once in the month of December? The answers to both questions lie in the very first paragraph of that sermon:

There is some probability that this is about the season of the year when the Saviour was born. A considerable part of the Protestant Christian world regard the 25th December as the time of his nativity; and devote that day to a celebration of the interesting event. The precise day however in which the angel uttered the joyful words of the text is probably unknown and will always remain so to the inhabitants of this world.

He based this observation on scripture. Had the exact date of that event been important, Hitchcock reasoned, the Bible would surely have stated as much. Why then was there no such statement in Holy Scriptures? Likely, he reasoned, it was "that men might not carry the observance of such a season to excess as they are prone to do in such instances."

So it seems that Edward Hitchcock was not inclined to make a great to-do about Christmas Day, whenever it might be. But Reverend Hitchcock did not mean to suggest that the birth of Christ was unworthy of celebration.

"to commemorate the birth of the Saviour in a religious manner is consonant with scripture and reason. It called forth the song of angels, glory to God in the highest - peace on earth and good will to men, and surely it ought to draw forth a responsive song from the hearts of man.

And that is about all Reverend Hitchcock ever wrote or preached about Christmas Day. The remainder of that one sermon, some twenty pages in its original form, was devoted to a description of the world as it was before Christ's birth and the change wrought by the arrival of the Christ child:

O what a joyful event is the birth of such a Saviour! Good tidings of great joy it is indeed to all people who have received it. Break forth into joy, sing together, ye waste places of Jerusalem: for the Lord hath comforted his people, he hath redeemed Jerusalem: for the Lord hath made bare his holy arm in the eyes of all the nations. Glory to God in the highest peace on Earth good will to men.

Did the Hitchcock family celebrate Christmas? If they did, there is no mention of it in their letters. Thanksgiving, on the other hand, was observed and its celebration was referred to in a number of the family's letters. Hitchcock wrote two sermons specifically for Thanksgiving Day, one entitled "The Works of God," the other "Prosperity the Ruin of Mankind."

See "Sermons of Edward Hitchcock 1819-1862," my transcription of Hitchcock's sermons, to read the full text of his one sermon about Christmas.

September 28, 2023

VERMONT GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF 1861?

In March 1857 Edward Hitchcock received a letter from Vermont Governor Ryland Fletcher offering him an appointment as State Geologist with the charge of carrying out a comprehensive geological survey of the Green Mountain State. This was the second such request he had received in that state, the first coming some 13 years earlier from Governor William Slade. Hitchcock actually accepted that first offer, but days later was forced to withdraw when the Board of Trustees appointed him third president of Amherst College.

The sixty-four-year-old Hitchcock had retired from the presidency of Amherst College in 1854 and was teaching only part-time when he received the letter. In frail health and with an ailing wife to care for, he might have been expected to decline the appointment. But he accepted and immediately began plans for the survey. It would be no sinecure: Vermont was nearly as large as Massachusetts with far more rugged terrain.

Shortly before the beginning of the first field season of the survey, Hitchcock made a wise move. He added three younger, more fit men to his team, his sons Edward, Jr., and Charles H. Hitchcock, and native Vermonter Albert D. Hager, an experienced geologist. But within weeks of embarking on the survey, the senior Hitchcock returned to Amherst exhausted, leaving the remainder of the field work for the Geological Survey of Vermont to his sons and Albert Hager.

Nearly three years later, with all the field data before him, Edward Hitchcock, Sr., began work on the final report that would be submitted to the Vermont legislature. By his own reckoning he spent a year on that work. In many ways it was the capstone of his career as a geologist, allowing him to integrate what he had learned over a lifetime about rock and mineral types, mountain building, erosion, deposition, metamorphism, and paleontology. The complete report, two volumes totaling some 650,000 words, received critical acclaim from scientists of his day and later.

Over one-hundred-twenty years later, University of Vermont geographer Harold A. Meeks published Vermont's Land and Resources (New England Press, 1986). Meeks was a highly regarded authority on the state's history. But in his book, he made a surprising statement about that 1861 geological survey:

Nearly a thousand pages were devoted to an exhaustive compilation of all the known knowledge of Vermont's natural resources, even to a discussion of the relative value of human and cow manure for fertilizer. This report was referred to often as Hitchcock's Geology of Vermont because three of the four authors commissioned by the State Legislature were surnamed Hitchcock. The report actually was done under the direction of Mr. Albert D. Hager who compiled the many reports, probably did the editing, and saw to the publishing of the work. Hager, of Proctorsville, Vermont, also wrote much of the material, although his name is seldom mentioned.

Was Meeks correct in this startling assertion? Had Edward Hitchcock been unfairly credited with the bulk of the work and Albert Hager slighted? Should the report have been called Hager's Geology of Vermont? The answer seems perfectly clear to me.

First, the State Legislature commissioned only Edward Hitchcock, Sr., to carry out the survey in his role as State Geologist. The act of the Vermont legislature that created that position empowered him to select his own assistants which he did shortly before the field work began.

Second, the field work was carried out primarily by Charles Hitchcock and Albert Hager working as a team over the course of three field seasons.

Third, Edward Hitchcock, Sr., and Charles Hitchcock wrote about ' of the report. Albert Hager authored two sections, "Economic Geology" and "Scenery," totaling about 20% of the entire work. Of the 38 color plates in the report, Charles Hitchcock executed 17, Albert Hager, 21.

Fourth, Edward Hitchcock gave Albert D. Hager generous credit for his role in the project, both in the field and in the printing phase. Hager is cited more than thirty times in the report and his initials appear several hundred times next to data collected by him.

What might account for Professor Meeks' conclusion that Albert Hager deserved most of the credit for the survey and the report? Probably the wording of the foreword led Meeks astray. Hitchcock wrote, "The Principal of the Survey desires to state, that the publication of this Report has been entirely under the direction of Mr. A. D. Hager." Hitchcock was referring to the printing of the report, not the direction of the overall project nor the writing and editing of the written report.

For more information on Hitchcock's geological survey of Vermont, please see pages 286-7 of my Hitchcock biography, All the Light Here Comes from Above: The Life and Legacy of Edward Hitchcock (Unquomonk Press, 2021).

I also invite you to read my article, "Against the Odds: Edward Hitchcock and the Vermont Geological Survey," in the Summer/Fall 2023 issue of the journal Vermont History, pp. 103-9.

December 30, 2022

HITCHCOCK'S DINOSAURS IN THE NEWS

One of the greatest frustrations Edward Hitchcock faced in his fossil footmarks research was the near total absence of skeletal remains of the creatures that made those tracks in stone. How was it possible to form thousands of tracks in the sandstone of the Connecticut River Valley, yet leave almost no fossilized bones? Such relicts would have helped Hitchcock describe the trackmakers with more confidence and perhaps dispel some of the skepticism his findings met in the popular media of his time.

The search for skeletal remains of New England dinosaurs went on after Hitchcock's death and continues to the present day. And some of the results have been exciting.

Professor Mignon Talbot (1869 - 1950) and the skeletal remains of

Podokesaurus holyokensis

In 1910, nearly half a century after Hitchcock's death, Mount Holyoke College geologist Mignon Talbot made a spectacular discovery. While walking barely a mile from campus, she came across remains she immediately recognized as a fossilized dinosaur skeleton. Podokesaurus holyokensis, as Professor Talbot named it, was a three-foot herbivore that was likely one of Hitchcock's trackmakers. In October 2022, in a ceremony at the Massachusetts State House in Boston, that very skeleton was unveiled and a declaration read by Governor Charles Baker establishing Podokesaurus holyokensis as the Bay State's official State Dinosaur. As I gaze on that photo of Governor Baker and others gathered around the specimen, I cannot help but imagine the spirit of Edward Hitchcock hovering over the proceedings, smiling.

Photo: Ashley McCabe, CNN

In 2021 another Mount Holyoke professor, paleontologist Mark McMenamin, found a boulder at a University of Massachusetts construction site in Amherst that he recognized as the humerus of a large predatory dinosaur. As yet unnamed, it is likely related to Cryolophosaurus, known from remains found in Antarctica.

While Edward Hitchcock is often associated with Massachusetts, he did much of his footmark research in Connecticut - in fact, there are more known localities for dinosaur tracks in the Nutmeg State than in the Bay State. And just over fifty years ago, Connecticut had the foresight to preserve hundreds of tracks unearthed at a construction site in a former quarry in Rocky Hill, now known as Dinosaur State Park. In 2017 one of the creatures from the Rocky Hill site, Eubrontes giganteum, was chosen as the Connecticut State Dinosaur. The tracks were among those reported by Hitchcock in his very first paper on the subject in 1835. He originally designated it Ornithichnites giganteum, but changed the generic name to Eubrontes a decade or so later.

These relatively recent findings are great news for 21st-century dinosaur enthusiasts. For all we know, there may be more dinosaur remains lying right beneath our feet as we explore the New England countryside nearly two centuries after Professor Edward Hitchcock made his earliest discoveries.

April 19, 2022

THE BATTLE OF THE TITANS

or

"The Agassiz and the Ecstasy"

The lives of Edward Hitchcock (1793-1864) and Louis Agassiz (1807-1873) intertwined again and again from 1840 to 1864. Between these two titans of American science there was mutual respect and admiration, to be sure, but there were stark differences as well, differences in interests, philosophies, and public personas. The pair seemed to circle each other in those years, like two boxers in a ring, ready at any moment to receive or deliver a blow.

Edward Hitchcock lived his entire life in western Massachusetts - his formal education was limited to six years at Deerfield Academy. He taught for more than thirty years at Amherst College where he was appointed President in 1845. He is best known for his pioneering research in ichnology, the study of fossilized tracks, a discipline he named and single-handedly elevated to respectability in paleontology.

Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz was a Swiss native who studied natural science at universities in Switzerland and Germany before earning an M.D. from the University of Munich. He is best known for his 1840 landmark work, Études sur les Glaciers, in which he proposed that much of the earth's surface had been covered with continental glaciers during the Pleistocene Era. In 1841 Agassiz emigrated to America and spent the rest of his life at Harvard University where he carried out exhaustive anatomical studies of sea creatures, fishes and mollusks in particular. Late in life he devoted much of his energy to the development of Harvard's natural history collections, preserved today as the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology.

For Hitchcock, reading Agassiz's treatise on glaciers was nothing short of an epiphany. By his own admission his eyes were open by Agassiz's thesis, and much of the surficial geology of Massachusetts that he had been studying and surveying at last made sense to him. Hitchcock was generous in his praise of Agassiz, citing the man and his works at least eighty times in his major geological writings. Agassiz on the other hand cited Hitchcock only six times in all his works, and almost exclusively in footnotes or bibliographies.

Louis Agassiz spent much of his life in the limelight. His work, his travels, his personal life, were subjects of constant interest in the newspapers of his time. Agassiz did everything he could to thrust himself into the public eye. He wrote letters to editors full of humor and vitriol toward other scientists. He paraded around in public, wining and dining, often to excess. And he built up his collections at Harvard as much it seems as a monument to himself as a contribution to science.

Agassiz seemed to revel in controversy, taking every opportunity to speak out on a range of subjects, knowing that for many both in the scientific community and in the public, his word was gospel. He claimed to be deeply religious, employing arguments based on Holy Scripture and what he regarded as Christian fundamentalism. But he was a racist and bigot, adapting Bible passages to fit his prejudices about human origins.

By contrast, Edward Hitchcock seems bland in personality and in public persona. He lived a quiet life, he valued home and family, and he wore his Christianity on his sleeve, living out the principles of his faith. Agassiz was flamboyant, often crude, a drinker and a womanizer, while Edward Hitchcock was a soft-spoken, self-deprecating teetotaler, utterly devoted to his wife and children. Not that Hitchcock was uninterested in his standing in public opinion, but he quietly accepted criticism and even scorn from non-scientists, trusting that his research and writings could speak for him (although his conflict with Dr. James Deane may be an exception, the one time in his life when it might be said that he "lost it").

Agassiz has long stood on a high pedestal in the history of science. But a recent biography by Christoph Irmscher (Louis Agassiz: Creator of American Science, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013) suggests that much of the credit Agassiz has been given for some of his works, particularly Études sur les Glaciers, is undeserved, that he largely repeated the views of others, happy to take credit for it as original to him.

And despite his vast knowledge of animal anatomy and paleontology, Agassiz fought Darwinism tooth and nail, largely on religious grounds, contending that, "The connection of faunas is not material, but resides in the thought of the Creator."

It is true of course that Edward Hitchcock also recoiled at Darwin's hypotheses on natural selection. He wrote forcefully of his objections to those notions, both religious and scientific. And yet, late in life, Edward Hitchcock seemed to admit the possibility of a crack in his defenses against Darwinism, even suggesting in his last year that natural selection might be a part of God's creation, like any other law of nature.

Louis Agassiz, on the other hand, never even hinted that he could accept Darwinism on any level. And Agassiz lived more than a decade after Hitchcock's death, in a time when Charles Darwin and his revolutionary ideas had become widely accepted in science.

In a list of the foremost scientists of 19th century America, Louis Agassiz would no doubt rank very high, perhaps number one, with Edward Hitchcock well behind. But Agassiz's reputation has taken more than a few hits in recent times amid questions about his personal life, his racial attitudes, and his scientific integrity. By contrast, Edward Hitchcock's character has never been in question and his star as a scientist has only risen in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

See Chapters 14, 24, 25, and 29 of All the Light Here Comes from Above: The Life and Legacy of Edward Hitchcock for further discussion of the sometimes contentious relationship between Edward Hitchcock and Louis Agassiz.

October 22, 2021

FLATTENED PEBBLES CLEFT BY TITAN'S SWORD

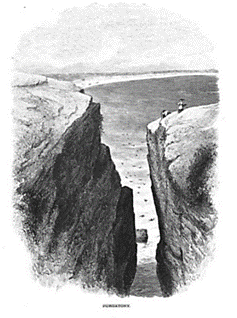

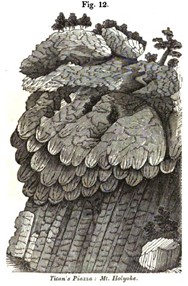

Purgatory Chasm, Middletown, RI

(Source: Picturesque America, 1872)

On the 13th of May, 1832, Edward Hitchcock stepped from a hired carriage along the rockbound seashore at Middletown, Rhode Island, a few miles east of Newport. He was immediately enthralled by the wild scene before him, wind whipping off the Atlantic driving waves into several wedge-shaped fissures in the ledge resulting in a virtual explosion of seawater and foam. He wrote of the site,

In one spot, in a high rocky bluff, two of these fissures occur not more than 6 or 8 feet asunder; and the waves have succeeded in the course of ages, in wearing away the intervening rock, so as to form a chasm about seven rods in length, and 60 or 70 feet deep; the sides being almost exactly perpendicular. This chasm is called Purgatory; and the waves still continue their slow but certain work of destruction.

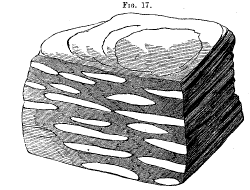

While that dramatic rock formation and the wild seacoast setting were naturally of great interest to Professor Hitchcock, what especially whetted his curiosity on that day was the rock that made up those ledges. It went by the very apt name of "puddingstone," for it consisted of a dense substrate much like pudding, but pudding containing many lumps. The lumps were smoothed pebbles ranging from a few inches to a foot long and displaying a variety of colors suggesting different mineral compositions. Those pebbles were set in a matrix of fine-grained rock much as stones are set in mortar in a wall or foundation. Furthermore, the pebbles were flattened just as if some great weight had been placed on top of the rock, compressing them as well as the surrounding "pudding."

Talcose schist

(Source: Hitchcock et al., Report on the

Geology of Vermont, 1861)

Also of great interest to the professor were vertical cracks that passed through the rock, piercing both the pebbles and the surrounding cement, separating them cleanly. Hitchcock wrote, "The cross seams of this rock have divided the pebbles as completely as if cloven asunder by the sword of some Titan, and an end view of the rock thus divided presents a quite singular appearance." The professor was sufficiently impressed that he wrote of that "most remarkable" rock in three reports on his geological survey of Massachusetts, adding, "No one can view this phenomenon without enquiring immediately into its cause."

For a long while Hitchcock seemed to have lost interest in those "flattened pebbles cleft by the sword of Titan." But a quarter century later in 1859 the full significance of what he had observed on the coast of Rhode Island began to come into focus. Edward, his sons Charles and Edward, Jr., and geologist Albert D. Hager had undertaken another geological survey, this one for the state of Vermont. Much to his surprise, they found rocks in the Green Mountains very similar to those on the coast of Rhode Island. To be certain Edward and Charles returned to Newport to reexamine those curious puddingstones at Purgatory Chasm.

What those flattened pebbles and sharp clefts in the Purgatory puddingstone revealed, he concluded, were fascinating and important details on how rocks are modified by heat and pressure over millennia. Those pebbles, he now realized, were formed much earlier, perhaps millions of years before the puddingstone. Each was composed of minerals present in some ancient lake or sea, rolled and abraded to a spherical or elliptical shape, then deposited on the lake or sea floor surrounded by fine sand, silt, or mud. And then, perhaps millions of years later, that sedimentary rock was compressed under enormous heat and pressure, probably from hundreds of feet of rock accumulated above it. Finally, the newly created rock was fractured, possibly during cooling. The result was a metamorphic rock known as gneiss.

What Professor Hitchcock had stumbled upon that day in May of 1832 was what we know today as metamorphism, a term referring to a variety of effects that have occurred over the millennia, effects that deform, abrade, and often reshape rocks.

Hitchcock was not the first to describe metamorphism. Many earlier geologists such as James Hutton, Abraham Werner, and William Maclure had recognized the effects of heat and pressure on rock formations. Englishman Sir Charles Lyell, the most influential geologist of Hitchcock's day, seems to have been the first to use the term "metamorphic rock" in its modern sense in his 1833 Principles of Geology. But Edward Hitchcock is often credited as the first scientist to infer the details of the process from simple observation of gneiss in the field.

In 1861 Edward Hitchcock published his most detailed account of the phenomenon in the American Journal of Science in an article entitled "On the Conversion of Certain Conglomerates into Talcose and Micaceous Schists and Gneiss by the Elongation, Flattening and Metamorphosis of the Pebbles and the Cement." To many geologists of his day and later, that paper represented a milestone in the understanding of metamorphosis. Geologist J. Peter Lesley, in his memoir for Hitchcock read before the National Academy of Sciences in 1866 wrote,

"Hitchcock's theorem that gneiss is nothing more nor less than metamorphosed old conglomerates, wherein the pebbles have been pressed into laminae composed of sections of the original matrix, themselves also pressed flat and thin is a bold assertion [that] will demand abundant proof...It is consistent with the now accepted view of metamorphism by pressure, under the conditions of a moist, low heat...its ample discussion and copious illustration by Dr. Hitchcock and his son, in the pages of his report of the Geology of the State of Vermont, will remain a part of the classics of our science.

Nearly thirty years later Charles L. Whittle of the U. S. Geological Survey referred to Hitchcock's "revolutionary ideas concerning the production of gneisses from conglomerates by metamorphism" as a "most valuable contribution to the science of geology." In 1906, George P. Merrill, an early curator at the Smithsonian, wrote of Hitchcock's 1861 article, "This paper, as a whole, marks a long stride in advance along the line of metamorphism."

How does a 21st century geologist regard Hitchcock's views on metamorphism formulated more than a century-and-a-half ago? Tekla Harms, Professor of Geology at Amherst College, argues that Hitchcock was right in some respects, wrong in others. She believes he was correct when he suggested that conglomerates like the Purgatory puddingstone could be transformed by heat and pressure into schists and gneisses. But as to the exact mechanism of that transformation, she argues, on that score he was mistaken. The pebbles in that conglomerate were not subject to simple mechanical flattening and elongation as Hitchcock suggested, but to a process called pressure solution in which particles migrate from areas of high concentration to low concentration. Furthermore, while Professor Harms admires Hitchcock's observational skills, she takes issue with his assertion in that 1861 article that metamorphosed rocks undergo compositional change. She writes, "Hitchcock's observations and the conclusions he draws directly from observations are almost unfailingly sound and stand the test of time. His ideas in this paper regarding compositional change during metamorphism are not based on observation but rather are hypothetical. Here, he is less successful."

Early in his career in a discourse before scientists in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, Edward Hitchcock warned against "extravagant theories" based on mere conjecture. He added,

But the present constellation of European geologists are men of a very different stamp - men whose grand object is the collection of facts, and who are extremely cautious of hypothesis; adopting none, except such as seem absolutely necessary to explain appearances.

Edward Hitchcock was just such a "collector of facts" who was normally careful not to get too far ahead of the facts, not to tinker with vague theories insufficiently supported by observation. Perhaps in the matter of those fascinating puddingstones, he should have taken his own advice.

* * *

I wish to thank Professor Tekla Harms of the Department of Geology, Amherst College, Amherst, Massachusetts, for sharing with me her expertise and insights regarding Hitchcock's views on metamorphism.

September 1, 2021

I am not as a general rule a believer in the supernatural. Nevertheless, on a recent August day on the campus of Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, I could have sworn I saw before me an emanation of the spirits of Edward and Orra Hitchcock. Maybe the near record heat was responsible, but the vision quickly passed, and what at first appeared as an effusion from a wormhole in the space-time continuum turned out to be a close encounter of a more conventional kind with Emily Hitchcock and Sawyer Hitchcock, great-great-great-great grandchildren of Edward and Orra.

Emily Hitchcock, daughter of Valerie Walton and Edward Hitchcock of Methuen, Massachusetts, graduated from Smith in 2019. An Environmental Science and Policy major, she is currently working as an intern at Nasami Farm in nearby Whately, a nursery of indigenous plants operated by the Native Plant Trust. Pride in their Hitchcock forebears runs deep in Emily's family. While she shares her name with a noted Hitchcock forebear, Emily Hitchcock Terry, her parents actually had another Emily in mind, Emily Dickinson. Her sister, Sharlow, was named after their great grandmother and 1920s opera star, Myrna Sharlow Hitchcock. Emily first became interested in her Hitchcock forebears when she and her family attended the 2011 opening of an exhibit of the artwork of Orra White Hitchcock at the Mead Art Museum at Amherst College celebrating the publication of Orra White Hitchcock: An Amherst Woman of Art and Science by Daria D'Arienzo and Robert L. Herbert.

Emily's cousin, Sawyer Hitchcock, son of Daniel and Janice Hitchcock of Fishers, Indiana, graduated from Ithaca College in 2016, majoring in English while also starring on the college's cross-country team for four years. He is currently working on an organic farm in Indiana. He has two siblings, Evan and Amanda. While visiting with his cousin, Sawyer traveled around the Connecticut Valley to some Hitchcock landmarks including Memorial Hall Museum in Deerfield, the original Deerfield Academy building where Edward and Orra first met. I guessed that he was named after his great-great uncle, Dr. John Sawyer Hitchcock, but Sawyer wasn't sure how he came by the name.

The two young Hitchcocks wanted to know what had drawn me to study the lives of their forebears, so I described my meandering career path. I wanted to hear about their educational and career pursuits, and how they came to their similar interests in agriculture, sustainability, and natural science.

While reading All the Light Here Comes from Above, Sawyer had wondered what his famous nineteenth century forebears would think if they could travel through time to visit the world of 2021. We agreed that Edward and Orra would likely have been amazed at the technological progress all around them, but worried by the perilous state of Planet Earth.

To Edward Hitchcock science and technology were essential tools of human progress, full of promise, untainted by risks or dangers. The fruits of those endeavors he witnessed in his lifetime - expansion of the railroads, improvements in manufacturing, advances in agriculture and medicine - were in his mind unambiguous goods. Words like "environmental," "conservation," "pollution," and "sustainability" were not in his or anybody's vocabulary. In all Hitchcock's writings I find not so much as a hint that he saw any possible downsides to science and technology, not in the mining and burning of coal, nor deforestation, nor air or water pollution, nor species decline and extinction. The only reservation he ever expressed about science was its possible effects on faith in God, on trust in religion, on morality. One of his principle objections to Darwin's theories on evolution and natural selection was that they threatened to diminish the importance of God's creative power in the minds of people of faith.

If the spirits of Edward and Orra Hitchcock were hovering above us on that sweltering August afternoon, I feel certain their worries about the state of the planet would have been balanced by the realization that their sixth generation descendants were as passionate and committed to forging a brighter future for humankind in the twenty-first century as they were in the nineteenth.

See also The Hitchcock Progeny: Three Generations and The Descendants of Edward and Orra White Hitchcock.

July 15, 2021

Edward and Orra Hitchcock grew up in a time when horse, buggy, and wagon were the main modes of local transport. For longer journeys stages ran between major cities, although travel was slow and schedules sometimes inconvenient.

"The earliest I can remember about travelling facilities was the stage route through Amherst between Hartford & Hanover," wrote Edward Hitchcock, Jr., in his memoir. In the 1830s there was one stage a day, he recalled, alternating northbound and southbound. Horses were changed at Boltwood's Tavern. The journey to Hartford took 12 hours, to Hanover some 18 hours with an overnight stop. The stage to Worcester departed from Amherst at 2:00 am, arriving in Worcester at 2:00 pm.

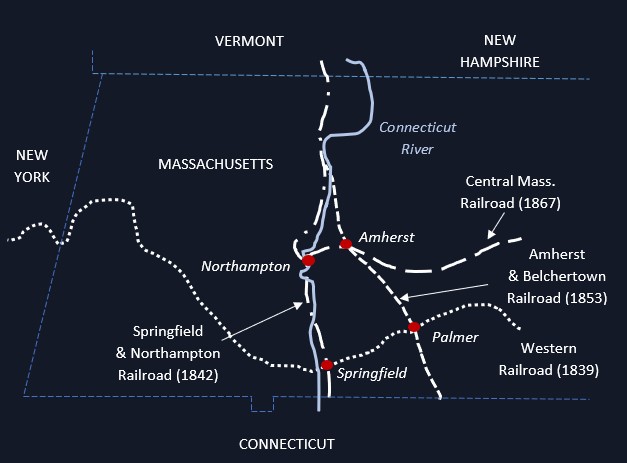

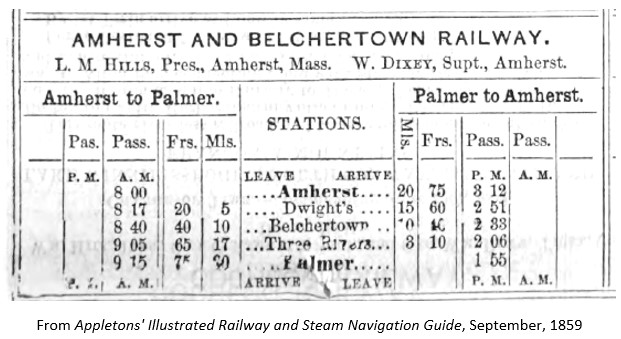

The arrival of the railroad soon made intercity travel considerably faster and more convenient. In 1839 the Western Railroad began operation from Boston to Springfield; three years later it was extended to Albany. In the same year the Hartford and New Haven Railroad began providing service to Springfield; by 1842 it was extended northward to Northampton. According to a published schedule, the trip from Springfield to Boston ran to three hours and fifteen minutes.

Despite an outcry from some of its citizens, Amherst was bypassed by both lines. Thus a trip to Springfield or Hartford began with a stage ride to Northampton; a trip to Boston required a stage from Amherst to Palmer to connect with the railroad. In his memoir Edward, Jr., writes of going the latter route on his first rail trip to Boston with Professor Charles B. Adams, probably in the 1840s.

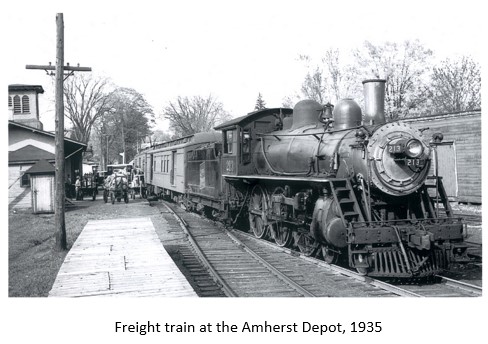

Amherst finally saw the arrival of direct rail service in May 1853 with the completion of the Amherst and Belchertown Railroad from Palmer to Amherst. The arrival of the railroad was anticipated with considerable excitement. In 1852 Jane Hitchcock, then 19, wrote to her brother, Edward, Jr., "The railroad is progressing...it will, in all human probability be finished as soon as next autumn. Perhaps by the time you get settled off in Michigan or California we shall have a great town here."

The trip to Palmer on the new line took about an hour and a quarter, the tracks passing just to the east of the Amherst College property. The depot constructed off Main Street (see the start of Chapter 26) stands to this day; the Amtrak "Vermonter" continued to travel that line until 2014.

With the completion of the Massachusetts Central Railroad in 1867 direct rail service was finally available from Amherst to Boston. But it was never competitive with the Western Railroad and ceased operation in 1917. Most of the track is gone, but the right-of-way still exists. The section through Amherst, now the Norwottuck Rail Trail, forms the southern boundary of the Amherst College campus today.

Edward Hitchcock, Sr., was a vocal advocate for expansion of rail service in the Connecticut Valley. He wrote several newspaper articles and letters to editors on the subject. And he was outspoken in support of the construction of the Hoosac Tunnel which by 1875 was providing rail service across northern Massachusetts.

Edward Hitchcock, Sr.'s first extended rail journey was to Washington, DC, in 1844. His anxiety about that trip was apparent in a letter written to his daughters Mary and Catherine in which he tried to reassure them that he was alive and well despite riots and murders in Philadelphia and a rail collision on that line just a few days earlier. Six years later he was an old hand at rail travel. In June 1850 as he and Orra journeyed through Europe, he wrote to his brothers from Dublin, "I have traveled a good deal by railroad and sometimes fast enough - 53 miles in 53 minutes!"

In December 1855 Edward embarked on a lecture tour in the Midwest, traveling by rail some 3000 miles in six weeks (see Chapter 23). He wrote to Orra on January 2, 1856, from Chicago, "I reached here before 10 o'clock this evening in safety having traveled 210 miles since noon. Most of the road all the way from Cincinnati is very rough and the cars rock about almost as much as our steamer did in crossing the ocean."

Edward's rail travel experience evoked a different sort of commentary in an 1848 sermon published by the American Tract Society entitled "Cars Ready." He described the scene at Union Station in Springfield as travelers waited anxiously for the arrival of their train, prepared to board and start their journey as soon as they heard the announcement, "Cars ready." But is the traveler ready for a far more consequential departure? wondered Hitchcock. "As he hears the summons, 'Cars ready!', 'Boat ready!', 'Stage ready!', let him be reminded how soon a more startling summons will break upon his ear: 'Prepare to meet thy God.'"

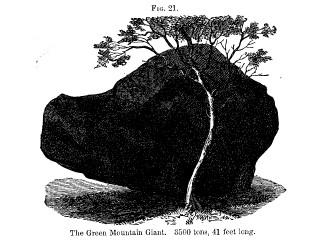

Edward Hitchcock was only 22 years old when he published his first scientific paper, a short article appearing in the North-American Review entitled "Basaltick Columns." It describes in just a few sentences a remarkable rock formation at the foot of Mount Holyoke in Hadley, Massachusetts, consisting of a series of vertical columns of basalt:

"These pillars are uniformly hexagonal prisms, varying in regularity, their sides being from eight to thirty inches wide. They form the side of the mountain for a distance of ten or twelve rods, and vary in height from sixty to more than a hundred feet. Their course inclines a little from the perpendicular, sloping gently towards the mountain."

Some years later Hitchcock dubbed this formation "Titan's Piazza"; another a short distance away on the shores of the Connecticut River he named "Titan's Pier." (It is said that the local names were previously the Devil's Piazza and Devil's Pier, but Hitchcock renamed them lest the Prince of Darkness be credited unjustly for part of God's Creation.)

Such geological curiosities are not unusual in volcanic rock; they occur frequently in the traprock ridges up and down the Connecticut Valley. Similar structures make up the famous Giant's Causeway in Northern Island. But the basaltic columns of Mount Holyoke are particularly well preserved and are rendered even more dramatic by the billowing tongues of basalt above that appear much like waves crashing on a beach.

s

The explanation of those curious hexagonal columns has to do with the cooling process in molten lava. Some parts of a lava flow cool before others. As they cool the rock contracts and fractures. Those fractures often radiate along parallel lines. When cracks meet they often form 120 degree angles which results in hexagonal or six-sided shapes, although five-sided and seven-sided columns are also common. As to the overhanging billows, they are likely the result of lava that cooled more slowly, allowing gravity to shape the mass, not unlike molten wax oozing down the sides of a candle.

I visited "Titan's Piazza" recently and was astonished at how beautifully those structures were preserved, just as Hitchcock saw them. The site is easily accessed from route 47, just a half mile or so south of the entrance to Skinner State Forest. But I could not help wondering how many visitors to Mount Holyoke ever got to see this remarkable formation. Then I read Hitchcock's description from his 1841 report on the geology of Massachusetts and realized I wasn't the first to have that thought:

"While the summit of Holyoke attracts crowds of visiters, but very few I have reason to believe go to this Piazza: yet I have never known any one visit it who was not highly gratified."

Then Hitchcock gave credit where he believed it belonged for this marvel:

...How can one, who has any taste for Nature

in her most curious aspects,

remain uninterested as he stands there...

gazing, and takes into his mind and heart,

With undistracted reverence, the effect

Of those proportions, where the Almighty hand

That made the worlds, the Sovereign Architect,

Has deigned to work as if by human art.

ROBERT L. HERBERT

1929-2020

One of the first sources I came across when I began my research on Edward Hitchcock was The Complete Correspondence of Edward Hitchcock and Benjamin Silliman, 1817-1863. I was at once awed by the scope of the manuscript that included transcriptions of some 250 letters between the two scientists. Equally impressive was the seventy-page introductory essay that placed Hitchcock and Silliman in the context of nineteenth century American science, tracing the evolution of their friendship and their views on science and religion over nearly half a century. The document was supported by no fewer than 670 footnotes, striking testimony to the thoroughness and attention to detail of its author, Robert L. Herbert, retired professor at Mount Holyoke College. At the time I was unfamiliar with Professor Herbert but guessed that he must be a geologist or historian of science. I was surprised to discover that that impressive opus was the work of an art historian.

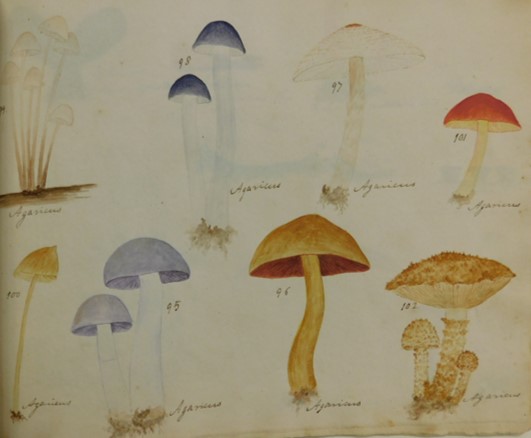

Professor Herbert produced at least eight works related to the Hitchcocks between 2008 and 2014. Besides Complete Correspondence he transcribed two travel diaries of Orra White Hitchcock, edited an exquisite reproduction of her watercolor album, Fungi, Selecti Picti, authored an article on the artistic inclinations of Edward Hitchcock in the Massachusetts Historical Review, and co-authored biographies of three important contemporaries of Edward Hitchcock, Roswell Field, James Deane, and Dexter Marsh, in collaboration with Sarah L. Doyle and others. In 2011 he and Daria D'Arienzo, then archivist at Amherst College, co-authored Orra White Hitchcock: An Amherst Woman of Art and Science, a handsome volume that includes a biography of the artist and a catalog of her paintings and drawings that appeared in an exhibit at the Mead Art Museum at Amherst College. (Bibliographic information for these works is provided below.)

Long before he became interested in Edward and Orra White Hitchcock, Robert L. Herbert was a distinguished professor of art history at Yale University where he earned a reputation as one of the world's foremost scholars on the Impressionist period. He developed his own distinctive approach to art history, examining in depth the lives of the artists and the social and political context in which they lived and painted, thus infusing a once sterile field with flesh and blood. Upon his retirement from Yale in 1990, Professor Herbert joined his wife, historian Eugenia Herbert, at Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley, Massachusetts. Both retired in 1997 but remained in South Hadley where he pursued his interests in the out-of-doors and New England history. There too he was introduced to Orra White Hitchcock and her art, then to her husband Edward and his scientific, religious, and artistic sentiments.

Professor Herbert scoured the letters and diaries of Edward and Orra just as intensely as he had examined the lives and works of the great Impressionists, searching for subtle clues to their personalities. In his introduction to Orra's travel diaries, he exhibits this talent most strikingly. Orra, he asserts in the introduction, was a dutiful mother and wife, a devout Christian, and a doer of good deeds. But those hand-written manuscripts, intended for no one but herself, provide a rare opportunity to fill out our understanding of her personality. "Hidden from view until now," wrote Herbert, "her more complete self finally emerges from her diaries."

Orra's wry, self-deprecating humor comes through on the first page of her account of their European trip in 1850. As she settled into a tiny cabin on their transatlantic steamer in Boston, she managed to ascend to her tiny upper berth only with the aid of "a little Yankee ingenuity" and "a little boosting from my husband." While a lover of art, Herbert notes, she paid more attention to the lavish furnishings of Windsor Castle and figures of Madame Tussaud's waxworks than to the classical works of art they saw at the National Gallery and the British Museum. She was a good-hearted Christian, to be sure, and was shocked at the squalid conditions of life in rural Ireland at the time, but regularly attributed poverty there and elsewhere in Europe to Catholicism. She was not immune to the prejudices of her time, likening the dark skin of the black workers she saw in Richmond, Virginia, to the filthy streets they cleaned.

The differences in the personalities of Orra and Edward, noted Herbert, were clearly on display in contrasting letters written to their children while vacationing on the coast of Maine. Of an excursion to Plum Beach with a party of friends, Orra wrote, "There were two gentlemen with us and we ducked and spattered each other and had the greatest frolic you can imagine." Meanwhile her sometimes saturnine husband, writing of the same trip, could only report to his children that he was suffering greatly, first from the cold on one of the coastal islands, then from the intense heat back on the mainland. Orra's cup, it seems, was always half-full; Edward's was half-empty.

Robert L. Herbert passed away in Northampton on December 17, 2020, at the age of 91, just a month before my book went to press. I immediately decided to dedicate the book to him - it seemed the least I could do. After all, hardly a day passed during the four years of my research that I did not consult one of Professor Herbert's works. They were invaluable to me and I will always be grateful for his scholarship.

Herbert, Robert L. The Complete Correspondence of Edward Hitchcock and Benjamin Silliman, 1817-1863: The American Journal of Science and the Rise of American Geology, transcribed and annotated with an introductory essay. Amherst College Archives and Special Collections, 2012. LinkReferences

________ and Sarah L. Doyle. The Dinosaur Tracks of Dexter Marsh: Greenfield's Lost Museum, 1846-1853. Mount Holyoke College Institutional Digital Archive, 2013. Link

________ and Sarah L. Doyle. Dr. James Deane of Greenfield: Edward Hitchcock's Rival Discoverer of Dinosaur Tracks. Mount Holyoke College Institutional Digital Archive, 2014. Link

________. Fungi Selecti Picti, 1821: Watercolors by Orra White Hitchcock (1796-1863). Northampton, Mass.: Smith College, 2011. The original album is held by Smith College Special Collections.

________, Sarah L. Doyle, Joel Fowler, Lynda Hodson Mayo, and Pamela Shoemaker. Roswell Field's Dinosaur Footprints, 1854-1880. Mount Holyoke College Institutional Digital Archive, 2013. Link

________. "The Sublime Landscapes of Western Massachusetts: Edward Hitchcock's Romantic Naturalism." Massachusetts Historical Review 12(2010): 70-99.

________. A Woman of Amherst: the Travel Diaries of Orra White Hitchcock, 1847 and 1850. New York, iUniverse, Inc., 2008.

________ and Daria D'Arienzo. Orra White Hitchcock: an Amherst Woman of Art and Science. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 2011.

In an 1823 sermon entitled "Duties of Children" delivered by Reverend Edward Hitchcock in Conway, Massachusetts, he reminded the youth of his church that nearly half of them would perish by the age of twelve (see Chapter 8). He was not exaggerating. Childhood was a hazardous time of life in those days; illnesses such as scarlet fever, diphtheria, typhoid fever, dysentery, and pneumonia were widespread and essentially untreatable. Edward and Orra lost two young sons, a 2-year-old in 1824 and an infant who died within a few hours of birth in 1832.

The six Hitchcock children that survived to adulthood lived remarkably long lives, three into their eighties, well beyond the average lifespan of Americans of that period. This may seem surprising considering their father's lifelong battle with poor health. Perhaps his children were fortunate to inherit their mother's vigor and emotional stability rather than their father's frailty and mercuric disposition.

As to the Hitchcocks' twenty grandchildren, seven perished before the age of six. But those who survived childhood lived relatively long lives, eight into their seventies or eighties. As to the third generation, Edward and Orra's ten great-grandchildren, nearly all were born after 1890. There were no childhood deaths in this generation. Eight of the ten lived longer than seventy years.

Aside from the scourge of childhood ailments, the three generations of Hitchcock descendants enjoyed many advantages. They grew up in stable homes in prosperous and forward-thinking communities such as Amherst, Massachusetts, Hanover, New Hampshire, and Orange, New Jersey. They were well-educated. Nearly all the males attended either Amherst or Yale while the females were enrolled at Mount Holyoke, Smith, Pratt Institute, or Cooper-Union. Several earned graduate degrees. Three male descendants pursued careers as scientists and college professors, two as engineers, two as medical doctors, two as attorneys, two as stockbrokers. At least five Hitchcock women were teachers, two artists, one a nurse, and one a social worker.

Several Hitchcock descendants earned reputations as leaders in their fields: Edward Hitchcock, Jr., in human anatomy and physical education, Charles H. Hitchcock in geology, Jane E. Hitchcock in community nursing, Edward B. Hitchcock in journalism, and Charles Hitchcock Allen in chemistry. Charles B. Storrs served in the New Jersey state legislature. Dr. John S. Hitchcock distinguished himself as head of the Massachusetts Division of Communicable Diseases during the influenza epidemic in 1919. At least three Hitchcock men served in the armed forces.

In The Descendants of Edward and Orra White Hitchcock, I present brief biographical sketches of each of the couple's thirty-eight children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. I am indebted to a number of archives and newspaper for photographs, obituaries, and other documents which are attached. Readers who find errors on those pages or have additional information to offer are welcome to submit them to me at robertmcmaster24 [at] gmail.com.

See also The Hitchcock Legacy Lives On.

1830-1833

Edward Hitchcock did nothing in life by halves. Each new task he undertook, each new assignment he accepted, he threw himself into with every ounce of strength he could muster. We can see this in the meticulous crafting of his sermons early in his career, his far-ranging travels in all seasons as an itinerant preacher, his intensive preparations for teaching chemistry at Amherst College, his ambitious pursuit of several state geological surveys, and his headlong rush to investigate those enigmatic fossil footmarks.

This trait in Edward Hitchcock, this indefatigable force, derived I believe from several sources within, intellectual curiosity, ambition, religious zeal, and a deeply-held conviction that his health depended on vigorous activity. Of course, throughout his adult life he was also convinced that his time was running out, his death was imminent. Of his "desponding nature" he wrote to Edward, Jr., late in life, "It is this trait in my character [that] has enabled me to do what little I have done as a literary man."

So it is no surprise to learn that within a month of receiving his commission to carry out the first geological survey of Massachusetts in 1830, Edward Hitchcock was off and running, notebook in one hand, mineralogical hammer in the other. Over the ensuing forty or so months, he visited every corner of the state, observing, recording, collecting specimens, and pondering the implications of his findings for his notions of geological history and God's plan for earth. It proved to be a life-altering experience for Hitchcock and a pivotal event for American geology (see Chapter 14).

How was it possible, we might wonder, that he could give up his college and family obligations for so many weeks over those four field seasons? The college apparently was happy to accommodate him. And Orra's steady hand and even temperament no doubt kept affairs under control on the home front. (Orra missed her husband, of that I have no doubt, but I can't help but wonder whether his absence may have made running the household a bit easier!)